Anti-Counterfeiting in the 21st Century. New Challenges and Perspectives

Stefano Ridolfi, IDArtScience Srl Rome, Italy

Counterfeiting as a Cultural and Economic Issue The forgery of paintings constitutes a matter of critical importance within the context of the art marke,a sector that, despite its aura of exclusivity, reveals itself to be highly susceptible to sophisticated forms of fraud. Counterfeiting undermines the integrity of cultural heritage and inflicts substantial economic damage. Fueled by the allure of high profits in contrast to low production costs and swift execution times, the practice proliferates especially in the realm of contemporary art. Here, the absence of traditional figurative elements and the higher reproducibility of works significantly facilitate both imitation and manipulation. Added to this is the expanding global demand for artworks, which further widens the profit margins for those operating within illegality, thereby confirming Cesare Brandi’s observation: falsification presupposes the attribution of value and arises wherever collecting takes place.

The data provided by the Italian Carabinieri Command for the Protection of Cultural Heritage are particularly telling: in 2023, 1,936 counterfeit works were seized, representing a 56% increase over the previous year. Of these, 1,340 were contemporary pieces, whose estimated market value would have exceeded 45 million euros. These figures are further supported by the IPERICO Report of the Ministry of Economic Development, which indicates that over the past decade, the total value of counterfeiting in Italy reached 6 billion euros, with more than 570 million goods seized.

Within the art market, counterfeiting typically manifests in three principal forms: imitations incorporating clearly recognizable new elements; reproductions explicitly declared as unauthentic; and, most problematically, copies introduced into circulation as original works. This last category represents the true core of the issue, as it deliberately seeks to deceive buyers. Although forgery is an ancient practice, it remains difficult to suppress due to the inherent complexity of detection and the ongoing evolution of reproduction techniques.

The issue is not merely economic in nature: the proliferation of forgeries compromises the entire artistic ecosystem, obstructing the work of scholars, appraisers, and institutions alike. Cultural heritage represents the tangible expression of our collective identity, and each artwork embodies a legacy of thought and beauty that transcends generations. To protect it is to preserve the memory of humanity and the transformative potential of art.

On a global scale, a 2019 report by Deloitte and ArtTactic estimated the value of the art market at approximately 67.4 billion US dollars, while revealing that between 30% and 50% of artworks in circulation are either forged or misattributed. Interpol’s Operation Pandora, launched in 2020, led to the seizure of over 41,000 fake or stolen objects, while the 2022 investigation “Infinito” uncovered a trafficking network involving 658 counterfeit works attributed to Francis Bacon, with a total estimated value exceeding 238 million euros.

The secondary market is not immune to risk either. A 2021 study by ArtNet showed that approximately 20% of artworks sold at auctions and galleries raise concerns regarding their authenticity. In Italy, the Nomisma Observatory identified a sector with a turnover of 1.46 billion euros, which rises to 3.78 billion when including related industries, employing around 36,000 individuals. Nevertheless, a substantial portion of the market remains hidden, concentrated in the hands of private collectors and existing beyond the reach of official analyses.

The Problem of Art Forgery The increasing sophistication achieved by contemporary forgers, who skillfully blend advanced technologies with historically authentic materials, has rendered the forgery of paintings a particularly insidious and multifaceted issue. Today, the ability to replicate not only the aesthetic but also the technical characteristics of original artists has reached a level of refinement capable of deceiving even qualified experts. As a consequence, the distinction between an authentic work and a counterfeit one has become a laborious, delicate, and complex endeavor. In this context, the demand for advanced scientific methodologies and technological instruments capable of more effectively supporting authentication processes has grown considerably.

Anti-counterfeiting measures have thus become a priority not only for collectors and buyers, but also for museums, galleries, and law enforcement agencies. A particularly significant example is represented by the Center for Art Law in New York, which organizes seminars and specialized courses to train legal professionals and experts in the identification of forgeries. Nevertheless, despite such initiatives, the fight against art counterfeiting remains hindered by fragmented international regulation and the often opaque nature of art market transactions. Further compounding this challenge is the rise in the financial value of artworks, which continues to attract criminal interest and incentivize the exploitation of legal and procedural loopholes.

Forgery is far from being a phenomenon of modernity; rather, it is deeply rooted in the history of art. Already in antiquity, alongside the market for original works, there existed a parallel market of copies intended for diffusion and educational purposes. In the Roman era, replicas of Greek statuary were widespread, just as in the Middle Ages, the trade in counterfeit relics flourished around pilgrimage sites. During the Renaissance, copying was regarded as a pedagogical tool and an act of homage to the master, while in the nineteenth century, it was also employed for purposes of conservation. In contemporary times, “authorial copies” executed with philological rigor—able to faithfully reproduce the brushstroke and chromatic palette of the original—have become increasingly appreciated. Yet the boundary between copy and forgery remains subtle and easily transgressed.

A well-crafted fake can pass even the most thorough examinations, particularly in the case of so-called “scientific copies”: reproductions produced by forgers proficient not only in painting techniques but also in chemistry and art history, who are capable of employing precisely those materials and methods documented in specialized treatises. New technologies further complicate the matter: 3D scanners and 2.5D printers now make it possible to replicate brushwork and surface texture with astonishing accuracy, yielding physical surfaces indistinguishable from the original. Initiatives such as those undertaken by “Haltadefinizione” and “Factum Arte” demonstrate the positive potential of these innovations, while simultaneously highlighting the risks posed by their possible fraudulent misuse.

An emblematic case involves the substitution of original paintings at the headquarters of RAI, Italy’s national broadcasting company, where works by Guttuso, Carrà, and Rosai were replaced with fakes. The investigation uncovered the theft of 120 artworks, resulting in economic damages amounting to millions for the public institution. The case caused widespread public outcry and revealed just how fragile the custodial chain for works of art can be, underlining the urgent need for unique and tamper-proof systems of identification at every stage of ownership transfer.

The 2017 Art & Finance Report published by Deloitte noted that 75% of market operators and collectors identified authenticity as the single greatest threat to the credibility of the art system. The core of the problem lies in the very real possibility that an artwork may be substituted with an identical copy without detection. Even in cases where the fraud is eventually uncovered, it is extraordinarily difficult to establish with certainty when and where the substitution occurred. The exponential growth of online art sales, where physical objects are purchased remotely, exacerbates this risk, as there is no direct or sensory engagement with the object itself.

The art market, often portrayed as a safe-haven investment akin to real estate or precious metals, is in fact significantly more vulnerable. Unlike a penthouse apartment with a view of the Colosseum, which is inherently and unmistakably identifiable, an artwork can be replicated with such precision that it becomes practically indistinguishable from the original. Its intrinsic identity is not self-evident; it can be copied, reinvented, or even “cloned.”

The entire infrastructure of the art market rests upon a fundamental presupposition: the uniqueness and continuity of the artwork’s identity over time, regardless of changes in ownership, restoration interventions, or exhibition history. Should this presupposition fail, the entire system becomes destabilized. The analogy of a world populated by human clones, in which the reliability of personal relationships would be rendered uncertain, conveys the disquieting implications of such a scenario. If a work attributed to a major artist can be surreptitiously replaced without detection, confidence in the entire art ecosystem collapses.

For this reason, the development of reliable instruments for the verification of movable artworks’ identity is imperative. Such solutions must be capable of withstanding even the most sophisticated forms of counterfeiting and of guaranteeing, under any and all conditions, that the object in question is indeed the one created by the artist. The credibility of the system, and the very survival of the art market itself, hinges on this certainty.

State of the Art in Anti-Counterfeiting: Available Solutions and Innovative Technologies

Throughout the history of art collection and conservation, efforts have consistently been directed toward identifying effective methods to prevent the substitution of a painting, or, more broadly, any valuable object derived from the artistic originality of a master. These methods have taken various forms, sometimes even imaginative in nature, but they must all possess a fundamental and indispensable attribute: the presence of an invariant property over time. That is, some component of the object must remain unaltered despite the inevitable physical degradation to which every material entity is subject.

Among the most immediate and cost-effective tools currently in use is the Object ID system developed by ICOM (International Council of Museums), which aims to define a minimum data set composed of objective information and calibrated photographs, equipped with colorimetric references, to characterize a work of art and facilitate its recognition in the event of theft. While this system has undeniable practical utility in identifying certain basic features of a work of art, it cannot establish with certainty whether the work in question is the original or a perfectly reproduced copy.

Over time, prestigious institutions and high-level private organizations have endeavored to develop increasingly innovative methods to protect artworks from forgery and unauthorized duplication. In general, anti-counterfeiting technologies fall into the following categories:

• Electronic technologies, based on associating an electronic device with the artwork. In such cases, it is the digital footprint of the device that is recognized. • Marking technologies, which use visible or ultraviolet light to highlight inscriptions on the reverse side of the artwork, serving as an identifying signature. • Chemical-physical technologies, which involve marking the artwork using instruments such as laser engraving. Here, the mark itself becomes the unique element associated with the work. • Mechanical technologies, which employ physical seals, wherein the applied seal becomes an identifying component. • Visual technologies, which rely on archived photographs taken prior to verification, subsequently compared to current images in order to establish correspondence with the object in question.

Nevertheless, all of these methods, in our view, are characterized by intrinsic limitations. They rely on elements that are added to the artwork. Anything that is applied to or associated with a work of art can be removed, altered, transferred to another object, or replicated. This makes it difficult, if not impossible, to guarantee the uniqueness of the artwork under examination.

A separate consideration must be given to methods based on images in the visible spectrum, including those taken at extremely high magnification, which are primarily employed due to their low cost of acquisition and analysis. Yet every visible characteristic on the surface of a painting, such as roughness, coloration or craquelure, can be copied, restored, or altered over time. Protective varnishes may yellow, pigments may shift in hue, supports may warp, and restorations may significantly alter both the chromatic and textural features of a painting. Furthermore, oil-based paintings darken over time and develop surface cracks (craquelure), which vary from work to work. These evolving traits make it impossible to attribute the role of temporally invariant indicators to such features.

In conclusion, none of the existing methods is capable of establishing with absolute certainty whether the artwork before us is the same one registered in law enforcement databases, included in a private or public collection, listed in a foundation’s catalogue, or archived by a qualified expert. Nor can we be certain that it is the very work originally acquired by a collector and, for instance, stored in a bank vault.

We may therefore summarize the main needs of the art market, which, at present, no existing procedure or technology can fully satisfy:

• How can it be demonstrated, with scientifically statistically defined probability, that a painting has not been forged? • How can an owner be assured that a recovered painting is indeed the one that was stolen from them? • How can an artist guarantee the authorship of their work in perpetuity, ensuring that their corpus is never contaminated by fakes? • How can we be certain that a painting loaned for an exhibition is the same one that will be returned? • How can we trust that a work certified or attributed by a foundation or an expert is indeed the specific object for which the attribution was issued? • How can we protect an art investment from a loss of value following the discovery that the work has been replaced by a forgery? • How can we be assured that a painting temporarily exported from national territory is the same one that returns in the country?

nd so on, with a potentially infinite number of scenarios that expose the current limitations in identifying a work of art in a scientifically rigorous manner, one not based on subjective opinions or expert viewpoints alone.

It therefore becomes necessary to develop a method, procedure, or criterion that is intrinsic to the work of art to be protected, non-removable, and as invariant over time as possible. The work of art itself must become the bearer of its own credentials: if those credentials fail to correspond, the forgery is automatically detected.

It is precisely within this context that the work of the innovative startup IDArtScience finds its rationale. With the support of a proprietary patent and funding obtained through the Pubblic Grant Start Up DTCLazio (BUR Lazio, 25/01/2022, “first-ranked project”), which supports innovative enterprises in the field of cultural heritage technologies, the startup has developed a system that is genuinely resistant to forgery.

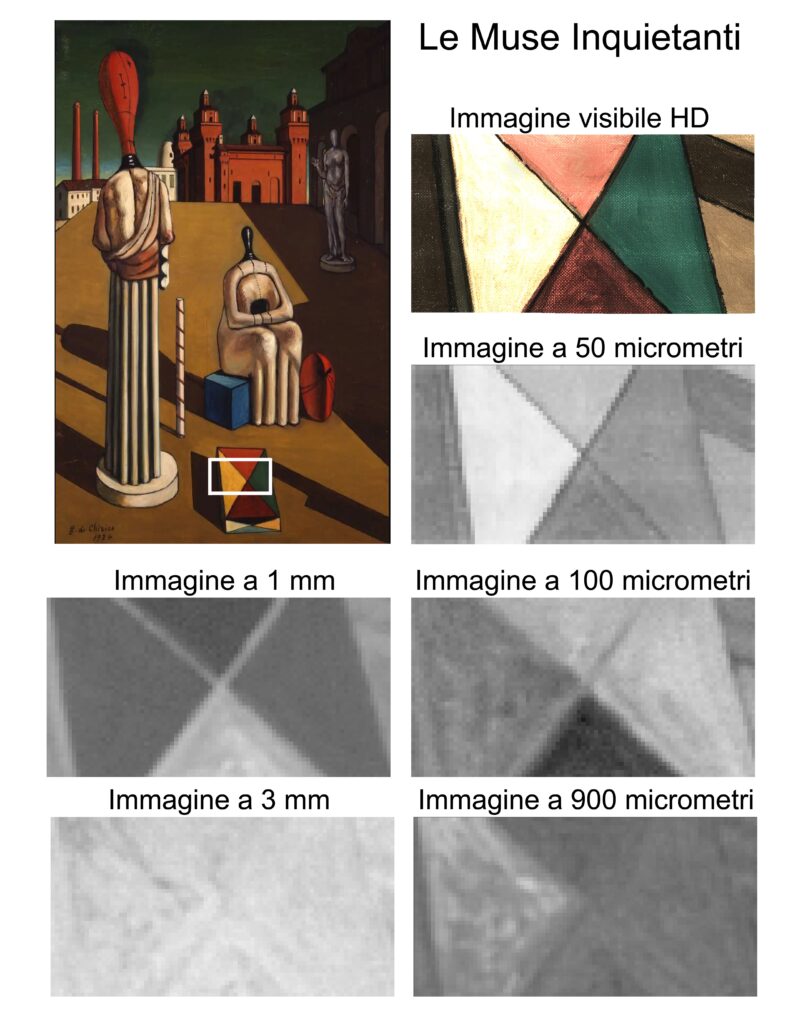

The foundational concept is that only features intrinsic to and hidden within the artwork can be considered truly unforgeable. The properties to be protected must not be visible or accessible: they must reside in the deepest layers of the artwork and be as resistant as possible to variations over time. A basic understanding of materials science and historical techniques has led the researchers to identify two properties that remain fundamentally constant over time: first, the elemental composition (not molecular but atomic) of the materials used, which is not affected by color shifts or surface degradation; and second, the stratigraphy of the work—that is, the sequence from the preparatory layers to the final protective varnish, and more precisely, the ratios between the thicknesses of these layers.

Even in the event of invasive restoration, such as relining with heat using a thermocautery, the ratios between the thicknesses of the pictorial layers tend to remain consistent, even if their absolute values might vary.

The innovative contribution of IDArtScience lies in having conceived and patented a model capable of correlating surface information (acquired through multiband imaging) with data from the internal layers, obtained through X-ray analysis. This correlation is achieved in a completely non-invasive manner, without introducing any foreign element, and allows the painting to be rendered unforgeable. The study spanned many years, culminating in a number of scientific articles addressing the theoretical aspects of the research. These are cited in the bibliography.

In extreme cases, the method is robust enough to enable the identification of a painting even if its surface were completely overpaintend. The information regarding the internal stratigraphic ratios and elemental composition would, in fact, remain intact.

Once the correlation between the surface and internal layers has been established, the resulting HASH of the analysis is saved onto the Blockchain, serving both as a timestamp and as a forgery-proof guarantee. This process safeguards the entire operation from any subsequent manipulation.

The date on which the HASH is registered on the Blockchain thus becomes the precise moment when the painting is rendered, in objective terms, unforgeable. Not even IDArtScience’s own operators could alter it thereafter. It is, effectively, akin to depositing the painting’s identity with a notary public.

A clear example of this technology’s application is offered by the Fondazione Giorgio e Isa de Chirico, which has chosen to adopt this innovative solution in a pioneering and original fashion.

The underlying problem is well known: once a painting is examined by a scientific committee and attributed to the master, it is returned to the owner with a certificate of attribution. However, the burden of preserving and protecting the artwork falls entirely upon the owner. This leads to a crucial question: how can we guarantee, in a scientifically irrefutable manner, that in the event of future transfer of ownership, the painting is indeed the same one that was originally studied and attributed?

The possibility of associating the attribution certificate in a unique and immutable way with the HASH recorded on the Blockchain, generated following the application of the patented IDArtScience procedure, makes the connection between the certificate and the physical painting both indissoluble and permanent.

This concrete application of the IDArtScience patent represents a significant and thus far unique development among foundations dedicated to safeguarding and promoting the artistic and intellectual legacy of an artist.

The unique identification of a painting through the patented procedure developed by IDArtScience may be carried out directly at the headquarters of the Fondazione Giorgio e Isa de Chirico, following a favorable opinion by the Foundation’s Scientific Committee and the official archiving of the artwork. The HASH resulting from this identification process is delivered together with the artwork. The full results and documentation remain available to the owner and are also archived by the Foundation, which thus retains the ability to verify the identity of the work attributed to the master at any time.

The operations envisaged by the patent are entirely non-invasive, do not pose any risk to the physical integrity of the artwork, and can be completed within approximately two hours at the Foundation’s premises. Any subsequent verification to confirm the authenticity of the attributed work can be conducted in roughly 45 minutes, even at the site where the work is stored.

In conclusion, in light of a comprehensive analysis of all existing technologies, the system proposed by IDArtScience emerges as the most robust solution available for ensuring the secure recognition of a work of art under any condition. This is a technology that finally enables the safeguarding of a work’s uniqueness across all the scenarios previously described.

It represents an effective deterrent against theft and forgery, for no matter how skilled the forger or how sophisticated the methods employed, the copy will be immediately and unequivocally recognized as such.

Bibliography

Lins, S.A.B., Gigante, G.E., Cesareo, R., Ridolfi, S., Brunetti, A.

Testing the accuracy of the calculation of gold leaf thickness by MC simulations and MA-XRF scanning (2020) Applied Sciences (Switzerland), 10 (10), art. no. 3582. DOI: 10.3390/app10103582

Cesareo, R., Ridolfi, S., Brunetti, A., Lopes, R.T., Gigante, G.E.<br>3D imaging of paintings by scanning with a portable EDXRF-device (2019) IMEKO International Conference on Metrology for Archaeology and Cultural Heritage, MetroArchaeo 2017, pp. 250-253.

Cesareo, R., Ridolfi, S., Brunetti, A., Lopes, R.T., Gigante, G.E. First results on the use of a EDXRF scanner for 3D imaging of paintings (2018) Acta IMEKO, 7 (3), pp. 8-12. DOI: 10.21014/acta_imeko.v7i3.549

Ridolfi, S. Gilded copper studied by non-destructive energy-dispersive X-ray fluorescence (2018) Insight: Non-Destructive Testing and Condition Monitoring, 60 (1), pp. 37-41. DOI: 10.1784/insi.2018.60.1.37

Ridolfi, S.

Portable EDXRF in a multi-technique approach for the analyses of paintings (2017) Insight: Non-Destructive Testing and Condition Monitoring, 59 (5), pp. 273-275. DOI: 10.1784/insi.2017.59.5.273

Sfarra, S., Ibarra-Castanedo, C., Ridolfi, S., Cerichelli, G., Ambrosini, D., Paoletti, D., Maldague, X. Holographic Interferometry (HI), Infrared Vision and X-Ray Fluorescence (XRF) spectroscopy for the assessment of painted wooden statues: A new integrated approach (2014) Applied Physics A: Materials Science and Processing, 115 (3), pp. 1041-1056. DOI: 10.1007/s00339-013-7939-1

Cesareo, R., Brunetti, A., Ridolfi, S. Pigment layers and precious metal sheets by energy-dispersive x-ray fluorescence analysis (2008) X-Ray Spectrometry, 37 (4), pp. 309-316. DOI: 10.1002/xrs.1078